calcium renal stones

- related: Nephrology, kidney stones

- tags: #nephrology

Potassium citrate

In addition to increasing fluid intake, potassium citrate is appropriate to prevent future calcium oxalate stones in this patient. Patients with chronic diarrhea and malabsorption are at increased risk for forming calcium oxalate stones for three reasons. First, because of the diarrhea and concomitant metabolic acidosis, urine citrate, an inhibitor of crystallization, is often reduced. In addition, volume depletion from the diarrhea decreases urine volume and thus increases the concentration of calcium and oxalate in the urine. Finally, in malabsorption, especially fat malabsorption as occurs in chronic pancreatitis, enteric calcium binds to fat as opposed to oxalate, leaving oxalate free to be absorbed and excreted in the urine. Although treatment should be based on the metabolic evaluation in this patient, his low urine pH and low serum bicarbonate level suggest that he has metabolic acidosis. Decreased systemic pH lowers urine citrate excretion. Supplementation with citrate as a base equivalent will help correct the acidosis and increase urine citrate, bind urinary calcium, and decrease the formation of calcium oxalate stones.

- pts with continued nephrolithiasis over 3-6 months should have drug intervention

- thiazide, allopurinol, potassium citrate

- This patient has had 2 episodes of nephrolithiasis separated by 4 years; he should undergo dietary interventions prior to considering drug treatment.

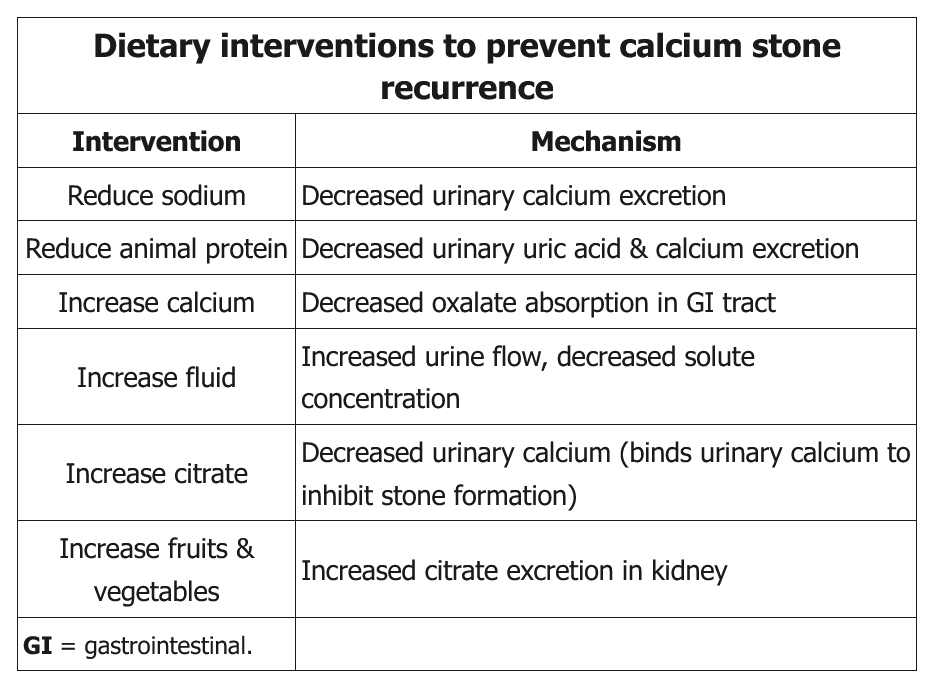

Dietary interventions can often correct the underlying abnormality and prevent recurrence.

This patient has a history of a calcium stone, the most common type of kidney stone. Patients with calcium stones are generally advised to do the following:

- Increase fluid intake – increases urinary flow rate and reduces urinary solute concentration

- Limit dietary oxalate – avoiding foods that contain high levels of oxalate, such as spinach, potatoes, and some types of nuts (eg, peanuts, cashews, almonds), helps reduce urinary oxalate levels and reduces the risk of calcium oxalate stones

- Limit sodium intake – increases renal sodium and calcium reabsorption, which reduces urinary calcium levels

- Reduce animal protein intake – animal protein increases urinary calcium levels and reduces citrate (citrate binds calcium and prevents stones)

- Increase dietary calcium – calcium binds oxalate in the gastrointestinal system and prevents gastrointestinal oxalate absorption; this reduces the risk of calcium oxalate stones

In the past, patients were counseled to avoid calcium, but high dietary calcium intake actually decreases the risk of stone formation. Dietary calcium binds oxalate within the gastrointestinal tract, thereby decreasing systemic absorption of oxalate and subsequent excretion into the urine. However, supplemental (vs dietary) calcium may actually raise the risk of stone formation. If patients have recurrent stones despite dietary measures, medications (eg, thiazide diuretics, potassium citrate, allopurinol) may be needed to alter urine composition.

Reduction of high purine–containing foods (eg, seafood, organ meats) decreases uric acid production and is recommended for patients with uric acid stones, not calcium stones.

If hypercalciuria is present, calcium excretion can be decreased by the use of thiazide diuretics. Because calcium excretion parallels sodium excretion, limiting sodium intake will also lower urine calcium. Unless excessive, dietary calcium should not be restricted because this will increase oxalate absorption. Oxalate excretion can be decreased by limiting foods high in oxalate such as nuts, cocoa, spinach, rhubarb, and beets. Potassium citrate or potassium bicarbonate will increase urinary citrate excretion. An additional benefit of potassium citrate is a decrease in renal calcium excretion, possibly related to preventing calcium release from bone.

Vitamin C increases urine oxalate excretion and would not have the desired effect of decreasing calcium oxalate stone formation.

Restricting dietary calcium intake in patients with hypercalciuria may paradoxically increase the risk of kidney stone formation by causing decreased binding of calcium with oxalate in the gut with increased absorption and urinary excretion of oxalate; therefore, dietary calcium should not be limited.